What's the Difference Between Audio Book and Read Aloud

The dual-route theory of reading aloud was first described in the early 1970s.[1] This theory suggests that two separate mental mechanisms, or cognitive routes, are involved in reading aloud, with output of both mechanisms contributing to the pronunciation of a written stimulus.[i] [ii] [3]

Lexical [edit]

The lexical route, is the procedure whereby skilled readers can recognize known words past sight alone, through a "lexicon" lookup process.[ane] [4] According to this model, every word a reader has learned is represented in a mental database of words and their pronunciations that resembles a dictionary, or internal lexicon.[three] [four] When a skilled reader sees and visually recognizes a written word, they are and so able to access the dictionary entry for the word and retrieve the information well-nigh its pronunciation.[ii] [5] The internal lexicon encompasses every learned word, even exception words like 'colonel' or 'pint' that don't follow letter of the alphabet-to-sound rules. This road doesn't enable reading of nonwords (e.yard. 'zuce'), though some phonological output tin can still be produced by matching the discussion to an approximation in the dictionary (e.g. 'sare' activating visually similar known words like 'care' or 'sore').[ane] [5] There is withal no conclusive evidence whether the lexical road functions every bit a direct pathway going from visual word recognition straight to speech product, or a less straight pathway going from visual word recognition to semantic processing and finally to oral communication production.[2]

Nonlexical or Sublexical [edit]

The nonlexical or sublexical road, on the other manus, is the process whereby the reader can "sound out" a written word. This is washed by identifying the word's constituent parts (letters, phonemes, graphemes) and, applying knowledge of how these parts are associated with each other, for example how a cord of neighboring letters audio together.[1] [iv] [five] This machinery can be thought of every bit a letter-sound rule organisation that allows the reader to actively build a phonological representation and read the discussion aloud.[ii] [three] The nonlexical route allows the correct reading of nonwords also as regular words that follow spelling-sound rules, but non exception words. The dual-route hypothesis of reading has helped researchers explain and understand various facts about normal and abnormal reading.[two] [4] [5] [vi]

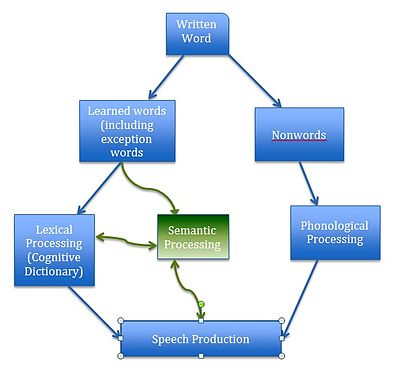

The mechanisms involved in dual-route processing, moving from the recognition of a written word to speech production.

Transparency of phonological rules [edit]

Co-ordinate to research, the amount of time required to principal reading depends on the language's adherence to phonological rules.[7] A written language is described every bit transparent when it strongly adheres to spelling-sound rules and contains few exception words. Because of this, the English language (low transparency) is considered less transparent than French (medium transparency) and Castilian (high transparency) which incorporate more consistent grapheme-phoneme mappings. This divergence explains why information technology takes more time for children to learn to read English, due to its frequent irregular orthography, compared to French and Spanish.[7] The Spanish language's reliance on phonological rules tin can business relationship for the fact that Spanish-speaking children showroom a higher level of operation in nonword reading, compared to English and French-speaking children. Similarly, Castilian surface dyslexics exhibit less impairment in reading overall, considering they can rely upon consequent pronunciation rules instead of processing many exception words every bit a whole in the internal lexicon.[7] The dual-road system thus provides an explanation for the differences in reading acquisition rates as well as dyslexia rates between dissimilar languages.[vii]

Reading speed [edit]

Skilled readers demonstrate longer reaction times when reading aloud irregular words that practise not follow spelling-sound rules compared to regular words.[viii] When an irregular word is presented, both the lexical and nonlexical pathways are activated but they generate conflicting information that takes time to be resolved. The decision-making procedure that appears to take place indicates that the two routes are not entirely independent from one some other.[8] This data further explains why regular words, that follow spelling-audio rules only also have been stored in long-term retentivity, are read faster since both pathways can "agree" about the issue of pronunciation.[5] [viii]

Attentional demands of each route [edit]

According to the electric current model of dual-road processing, each of the two pathways consumes unlike amounts of express attentional resources.[8] The nonlexical pathway is thought to be more active and constructive equally it assembles and selects the correct subword units from diverse potential combinations. For example, when reading the word "leaf", that adheres to spelling to sound rules, the reader must gather and recognize the two-letter character "ea" in order to produce the sound "ee" that corresponds to it. Information technology engages in controlled processing and thus requires more attentional capacities, which can vary in corporeality depending on the complication of the words being assembled.[viii] On the other mitt, the processing that takes place in the lexical pathway appears to exist more automatic, since the word-sound units in it are pre-assembled. Lexical processing is thus considered to be more than passive, consuming less attentional resources.[viii]

Reading disorders [edit]

The dual-route hypothesis to reading tin help explain patterns of data connected to certain types of disordered reading, both developmental and acquired.[9]

Routes impaired in surface and phonological dyslexia

Children with reading disorders rely primarily on the sub-lexical route while reading.[10] Research shows that children can decode non-words, letter by letter, accurately but with slow speed. However, in decision tasks, they have trouble differentiating between words and pseudohomophones (non words that sound similar real words only are incorrectly spelled), thereby showing that they had impaired internal lexicons.[10] Because children with reading disorders (RD) have both slow reading speeds and impaired lexical routes, at that place are suggestions that the same processes are involved in lexical route and fast naming of words.[10] Other studies have also confirmed this thought that rapid naming of words is more strongly correlated with orthographical noesis (lexical route) than with phonological representations (sub-lexical route). Similar results were observed for patients with ADHD.[10] Research concludes that reading disorders and ADHD have common backdrop: lexical route processing, rapid reading and sublexical route processing deficits too.[10]

Acquired surface dyslexia [edit]

Surface dyslexia was kickoff described by Marshall and Newcombe, and is characterized by the inability to read words that exercise not follow traditional pronunciation rules. English language is as well an example of a language that has numerous exceptions to the rules of pronunciation and thus presents a particular challenge to those with surface dyslexia. Patients with surface dyslexia may neglect to read such words equally yacht, or island for case, because they practice non follow prescribed rules of pronunciation. The words volition typically exist sounded out using "regularizations", such as pronouncing colonel equally Kollonel.[11] Words like state, and intestinal, are examples of words that surface dyslexia sufferers will not have a trouble pronouncing, equally they do follow proscribed pronunciation rules.[12] Surface dyslexics volition read some irregular words correctly if they are high frequency words such as "accept" and "some".[11] It has been postulated that surface dyslexics are able to read regular words by retrieving the pronunciation through semantic ways.[12]

Surface dyslexia is also semantically mediated. Meaning that there is a relationship between the discussion and its meaning and not only the mechanisms in how it is pronounced. People who suffer with surface dyslexia also have the ability to read words and non-words akin. This means the physical production of phonological sounds is non affected by surface dyslexia.[12]

The mechanism behind surface dyslexia is thought to be involved with the phonologic output of the lexicon and is besides oft attributed to the disruption of semantics. It is too hypothesized that three deficits cause surface dyslexia. The first deficit is at the visual level in recognizing and processing the irregular word. The second arrears may exist located at the level of the output lexicon. This is considering patients are able to recognize the semantic meaning of irregular words even if they pronounce them incorrectly in spoken give-and-take. This suggests the visual give-and-take form organization and semantics are relatively preserved. The third deficit is likely related to semantic loss.[xi]

While Surface dyslexia can exist observed in patients with lesions in their temporal lobe, information technology is primarily associated with patients who take dementias. Such as Alzheimer'due south or fronto-temporal dementia. Surface dyslexia is also a feature of semantic dementia, in which subjects lose cognition of the world around them.[12]

Handling of surface dyslexics involves neuropsychological rehabilitation. The aim of the treatment is to better the operation of the sub lexical reading road, or the patient'south power to audio out new words. Every bit well as the operation of the visual word recognition system, to increase the recognition of words. On a more micro level, treatment can also focus on the power to sound out individual letters before the patient goes on to increasing the ability to audio out entire words.[13]

Acquired phonological dyslexia [edit]

Acquired phonological dyslexia is a type of dyslexia that results in an inability to read nonwords aloud and to identify the sounds of unmarried letters. However, patients with this disability tin holistically read and correctly pronounce words, regardless of length, meaning, or how mutual they are, as long equally they are stored in memory.[2] [4] This type of dyslexia is thought to be acquired by damage in the nonlexical route, while the lexical route, that allows reading familiar words, remains intact.[2]

Computational modeling of the dual-road process [edit]

A computational model of a cognitive task is substantially a estimator program that aims to mimic human cognitive processing[5] [14] This blazon of model helps bring out the precise parts of a theory and disregards the ambiguous sections, as but the clearly understood parts of the theory can exist converted into a computer program. The ultimate goal of a computational model is to resemble human behavior as closely as possible, such that factors affecting the functioning of the program would similarly affect man behavior and vice versa.[14] Reading is an area that has been extensively studied via the computational model organization. The dual-route cascaded model (DRC) was adult to empathize the dual-road to reading in humans.[fourteen] Some commonalities between human reading and the DRC model are:[v]

- Frequently occurring words are read aloud faster than non-frequently occurring words.

- Actual words are read faster than non-words.

- Standard sounding words are read aloud faster than irregular sounding words.

The DRC model has been useful as it was also made to mimic dyslexia. Surface dyslexia was imitated by damaging the orthographic lexicon so that the program made more errors on irregular words than on regular or non-words, only equally is observed in surface dyslexia.[6] Phonological dyslexia was similarly modeled by selectively damaging the non-lexical route thereby causing the program to mispronounce non words. As with any model, the DRC model has some limitations and a newer version is currently being developed.[14]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d east Pritchard SC, Coltheart K, Palethorpe S, Castles A (Oct 2012). "Nonword reading: comparison dual-route cascaded and connectionist dual-process models with human information". J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 38 (5): 1268–88. doi:x.1037/a0026703. PMID 22309087.

- ^ a b c d e f grand Coltheart, Max; Curtis, Brent; Atkins, Paul; Haller, Micheal (1 January 1993). "Models of reading aloud: Dual-route and parallel-distributed-processing approaches". Psychological Review. 100 (4): 589–608. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.589.

- ^ a b c Yamada J, Imai H, Ikebe Y (July 1990). "The utilize of the orthographic dictionary in reading kana words". J Gen Psychol. 117 (iii): 311–23. PMID 2213002.

- ^ a b c d east Zorzi, Marco; Houghton, George; Butterworth, Brian (1998). "2 routes or one in reading aloud? A connectionist dual-procedure model". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Operation. 24 (4): 1131–1161. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.24.4.1131. ISSN 1939-1277.

- ^ a b c d e f g Coltheart, Max (2005). Margaret J Snowling; Charles Hulme (eds.). Give-and-take recognition processes in reading. Modeling reading : the dual-route approach (PDF). The science of reading : a handbook. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub. pp. 6–23. ISBN9781405114882. OCLC 57579252.

- ^ a b Behrmann, One thousand.; Bub, D. (1992). "Surface dyslexia and dysgraphia: dual routes, unmarried dictionary". Cognitive Neuropsychology. 9 (3): 209–251. doi:10.1080/02643299208252059.

- ^ a b c d Sprenger-Charolles, Liliane; Siegel, Linda S.; Jiménez, Juan Eastward.; Ziegler, Johannes C. (2011). "Prevalence and Reliability of Phonological, Surface, and Mixed Profiles in Dyslexia: A Review of Studies Conducted in Languages Varying in Orthographic Depth" (PDF). Scientific Studies of Reading. xv (6): 498–521. doi:10.1080/10888438.2010.524463. S2CID 15227374.

- ^ a b c d e f Paap, Kenneth R.; Noel, Ronald W. (1991). "Dual-route models of print to sound: Notwithstanding a skillful horse race". Psychological Research. 53 (1): xiii–24. doi:10.1007/BF00867328. S2CID 143907894.

- ^ Matthew Traxler (2011). Introduction to Psycholinguistics: Understanding Language Science. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN978-one-4051-9862-2. OCLC 707263897. [ page needed ]

- ^ a b c d east de Jong CG, Licht R, Sergeant JA, Oosterlaan J (2012). "RD, ADHD, and their comorbidity from a dual road perspective". Child Neuropsychol. eighteen (5): 467–86. doi:10.1080/09297049.2011.625354. PMID 21999484. S2CID 5326165.

- ^ a b c Coslett, H. B.; Saffran, Due east. 1000.; Schwoebel, J. (2002). "Knowledge of the human being body: A distinct semantic domain". Neurology. 59 (3): 357–363. doi:10.1212/WNL.59.3.357. PMID 12177368. S2CID 19647839.

- ^ a b c d Coslett, H. Co-operative; Turkeltaub, Peter (2016). "Acquired Dyslexia". Neurobiology of Language. pp. 791–803. doi:ten.1016/B978-0-12-407794-2.00063-8. ISBN9780124077942.

- ^ Brunsdon, & Coltheart. (2005). Assessment and Treatment of Reading Disorders: A Cognitive Neuropsychological Perspective. Lecture presented in Macquarie Academy.[ verification needed ]

- ^ a b c d Coltheart, Max; Rastle, Kathleen; Perry, Conrad; Langdon, Robyn; Ziegler, Johannes (1 January 2001). "DRC: A dual route cascaded model of visual word recognition and reading aloud". Psychological Review. 108 (ane): 204–256. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.108.1.204. PMID 11212628.

What's the Difference Between Audio Book and Read Aloud

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dual-route_hypothesis_to_reading_aloud

0 Response to "What's the Difference Between Audio Book and Read Aloud"

Post a Comment